The Cambridge Plan, Part 1

Some background on the planning, and socioeconomic, environment of Cambridge

“Incomparably beautiful in many things, miserably defective in others, Cambridge is still one of the most pleasant places on earth in which to live. Moreover, it is now perhaps the only true ‘University town’ in England. The question is whether it can control its own destiny in the face of a multitude of unplanned events that will certainly tend to change it.”

Holford and Wright, A Report to the Town and Country Planning Committee of the Cambridgeshire County Council, 1950.

Over the past few weeks, plenty of ink has been spilled on the government’s new proposed Cambridge Quarter, a suggested plan to expand the city by 250,000 residents over the next 17 years. Based on my – admittedly biased – viewpoint from Twitter, it seemed that the overwhelming majority of voices in support of the proposal were coming from outside Cambridge, and the majority of dissension from those within. Even my friend Julian Huppert, who is by no means a NIMBY, is concerned about growing the population at that rate.

I think Julian has little reason to be concerned, and in the next post I’ll examine the proposals in more detail and argue why. But for today it’s worth dwelling on this resistance, and attempting to understand its provenance. Cambridge is an otherwise liberal, progressive, pro-industry town with a lot of science, technology, cycling infrastructure, and a world-class university. This instinctual caution is, at first blush, an uncomfortable bedfellow.

A culture of preservation

…until you look at the history, and you realise that resistance to development in Cambridge is a long, noble, and codified tradition.

When, in 1948, Holford and Wright were invited by Cambridgeshire County Council to prepare a local plan for Cambridge, they entered a city poised for growth and expansion. The population of Cambridge had grown to around 86,000 in the city and an additional 17,600 in neighbouring villages, an increase of some 24 per cent between 1931 and 1948.

The planners were brought in, it seems all too clear, to stop it:

We believe that a rapid growth is likely to continue, and even to accelerate, unless special effort is made to prevent it. This effort seems to us both nationally and locally desirable … That there should be a resolute effort to slow down migration into the Cambridge district, and to reduce the high rate of growth so that future population should not greatly exceed present figures, is our first and main proposal and permeates all others.

A lot of what the original plan was concerned with was traffic congestion; it makes up close to half of the total plan. In particular, they are concerned with what the authors call the “spine road”, the road that begins in the north as Huntingdon Road and runs through town, over the Cam as Bridge St, changing its name three more times before emerging as Hills Road in the south. But much of the focus is also on land preservation, resisting industrial encroachment, some small development on the outskirts (eg Milton) and keeping density low and commercial activity to a minimum.

This plan was not imposed from above by some planners errant; Holford’s team was financed by the Cambridgeshire County Council and the work was mostly done from within the council’s planning department. It was prepared for, funded by, and embraced by the council. Its proposals relating to size were accepted by the committee when discussing the report:

The Committee were unanimously agreed on the necessity for limiting the growth of Urban Cambridge and accepted the Consultants’ proposals that endeavours be made by the Planning Authority to reduce the rate at which Cambridge is growing to reach a stable population figure of about 100,000 in the Borough and 120,000 - 125,000 in Urban Cambridge.

And in the eventual development plan, published in 1952:

The basic proposals of the County Council are:

(a) That Cambridge should romain predominantly a University town

(b) To reduce the rate at which the City is growing and to stabilise the population within the Town Map Area at not more than about 100,000 persons.

It also didn’t come out of nowhere; the preceding regional plan from 1934 makes reference to the “encroaching industrial developments” and the need to “guarantee this supremacy [of the college buildings]”. There was a clear understanding of the distinctive character of Cambridge, and the threat that industrialisation of the Fens posed.

It therefore doesn’t seem unreasonable to think that, in 1950, the County Council got what it always wanted: a plan expressive of a deeply conservative vision for what Cambridge ought to be. One that was regimented into the standard logic of preserving local character and protecting historical significance, something that becomes even clearer when we see how the plan was implemented. The Council, on recommendation from the Committee, agreed to:

seek “the support of the Ministry of Town and Country Planning and the Board of Trade be sought in diverting new mass production industry or large extensions of existing factories to sites outside Urban Cambridge”;

ask “Central Government Departments … to assist in reducing their demands on the Cambridge labour market”

and, finally, ask “the University and the Ministry of Town and Country Planning … to assist in examining methods whereby the rapid growth of the town can be checked”

This was a plan that was wanted, and the commitment to curtailing the population growth of the town was kept. The net result, 71 years later, is that Cambridge now has a population of some 146,000, just under a 70% increase, or roughly 0.75% population growth each year. Holford’s target has been overshot, of course, but, in absolute terms, not by much. Even to this day, the Cambridge green belt is still justified as helping “to preserve the unique character of Cambridge as a compact, dynamic city with a thriving historical centre”.

The speculative case for planning success, then, is that Holford’s prescriptions were crucial to the success of the University. Thus the key rationale for Holford’s conclusions: if the University were to grow, then it would need the space to grow into. The expansion of university buildings, especially the sorts of large scientific laboratories that the University, with its renewed emphasis on the natural sciences, would have to come at the cost of either a restricted population or the walkable local character and agglomeration effects beneficial to collegiate life. Holford, the University, the city and county councils, and the relevant Westminster departments, all chose the former. Without these protections, the argument goes, Cambridge would be a much less successful university, and city, than it is today.

But this feels like motivated reasoning. As we will see, Cambridge’s economy has been driven by the tech and biomedical startups that are spillovers from the University. The recruitment power for any academic institution is driven overwhelmingly by academic prestige and the availability of funding, not the local character of the town it sits within nor per se how walkable it is (though we’ll discuss that in part 2). It seems hard to imagine how a Cambridge 30% bigger (approximately the same size as Oxford), say, would lose enough of what makes it special to erode the prestige associated with 121 Nobel prizes.

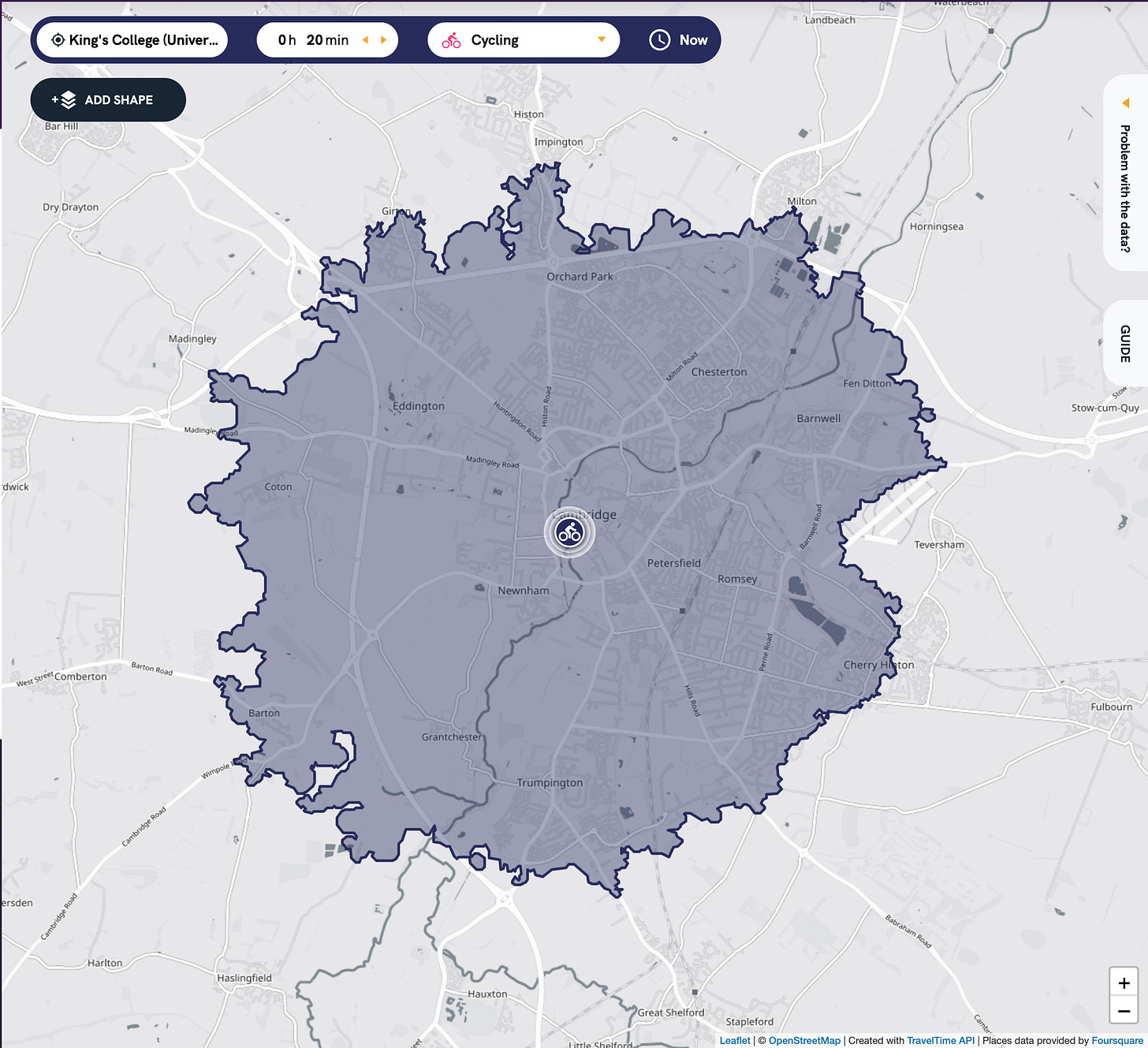

It’s also hard to imagine that newer University buildings, such as the West Cambridge site, could not have found other locations within a reasonable travel time. Here, for instance, is the 20 minute cycling radius from King’s College:

It stretches well into the neighbouring villages, and one imagines specific routes could go further still with dedicated cycle lanes and better bus infrastructure. And, at any rate, Cambridge could be quite a bit denser by building higher rather than building further out. (As it happens, the colleges and university already owned much of the land to the west of the city anyway, so it’s likely it would always have been built there.)

None of this is to say that there aren’t benefits to the university being concentrated within the town, and having access to grow and expand its facilities. There obviously are – agglomeration effects are one of the main reasons why I support greater densification of Cambridge and elsewhere. It simply seems unrealistic to assume that the non-Holford counterfactual results in a Cambridge with substantially retarded growth and a university with significantly less prestige. Especially given that the primary level of organisational infrastructure in Cambridge is the college, an institution explicitly designed to agglomerate; and the colleges certainly weren’t going anywhere.

So if it isn’t the planning that drove the economic success of modern Cambridge, what was it? In order to understand Cambridge, you need to understand its university.

The University of Cambridge, Science, and the Modern Cambridge Economy

The University of Cambridge took its modern shape in the period covering the 1830s - 1880s. Until that point Cambridge, like Oxford, had been predominately an ecclesiastical institution, training boys for entrance to the clergy. Between 1831 and 1840, fully a third of the matriculating Cambridge graduates were to be ordained as ministers in the Anglican Church.

Then a series of changes occurred that altered the university’s path quite radically. Pressure from a rapidly urbanising society, and a colonial infrastructure at the height of its powers, drove a greater need for administrators, teachers, civil servants, and other professionals. The ban on dissenters and nonconformists was revoked in 1856, as was the requirement that teaching staff be celibate and within the holy orders. The University was forced to introduce new professorships, libraries and lecture rooms to meet the challenge posed by the recently emerging redbrick universities in London, Manchester, Birmingham and Liverpool. This gradually began to introduce the thinking that the University could help prepare individuals for government and industry, rather than just the Church.

But it was the expansion of the natural sciences that truly gave Cambridge the edge it enjoys today. The mathematical tradition, strong in Cambridge at least since the Lucasian Professorship was established in the 1660s, proved to be a robust foundation for the teaching of the natural sciences. Cambridge offered scholarships for mathematics and the physical sciences, whereas Oxford offered none. The Natural Sciences Tripos were first introduced in 1848, and, perhaps importantly, the Cavendish Laboratory was founded in 1870. This lead to a chair in experimental physics in 1873, and from there the reputation of science in Cambridge, especially physics, was very strong; by 1937, nine cantabs had won the Nobel Prize in Physics. World War II compounded these advantages, by shifting resources over to research into radar, radioactivity, and other areas of applied physics valuable to the war effort. This research produced a plethora of new technologies, many of which were responsible for the shape and texture of the modern world, as well as the institutional knowledge and global expertise at how to develop and deploy them.

Which meant that by the time the personal computing revelation came around, Cambridge had the intellectual resources to capitalise. Herman Hauser, for instance, played a pivotal role in the founding of Acorn Computers in the late 1970s, a company responsible for pioneering home computing in the UK with machines like the Electron and BBC Micro. Acorn spun out ARM, which evolved into a global leader in microprocessor intellectual property, its designs powering billions of devices worldwide.

And that is just one story among many. Cambridge is full of similar companies, adjacent to the University, or attracted there because of it: Pye, Sinclair, CSR, Sepura, Microsoft Research, WorldPay, Red Gate, the games developer Jagex, the aerospace manufacturer Marshall’s, biotech companies Amgen, AstraZeneca, Napp, Bayer, and many many more all based a significant part of their UK operations or R&D from the city. Science, Engineering and Research professionals now make up roughly 20% of the workforce.

And so we can start to see a strange paradox emerge. A booming and buoyant commercial sector, a vibrant start-up ecosystem, a highly productive university and a stream of exceptional graduates ready to participate in the workforce on the one hand. A planning culture of caution, conservatism, maintaining local character, strict adherence to the Green Belt and the distinctness of settlement boundaries on the other.

It is possible that Holford was right, and that the University would not have flourished were Cambridge more populated, more spread out. But keeping the size of the town small seems neither necessary nor sufficient for the success of the University. Its success was driven in large part because of the Cavendish Lab, the resources and political impact of the physical sciences to the war effort, and the compounding effects of the prestige it gained through them. Those successes would be successes regardless of whether the town then grew. In fact, not growing is likely to have prevented even more success.

This does not seem lost on at least some members of the Cambridge planning ecosystem. Cambridge has, in fact, managed to achieve some planning successes recently. The Eddington development in the north-west of the city currently houses 700-odd people, and will eventually house 3,000, and over a million square foot of research facilities. Great Kneighton, to the south of the city, appears to be progressing well, and there have been some brownfield sites in the city centre that have been accepted. (I’m thinking specifically of the Park Street car park, but there are lots of other opportunities that, with some imagination, could work too.)

But this is in a city that has experienced jobs growth of 5, 6, 7% annually; in 2016 the council estimated that a further 34,000 homes would be necessary by 2031. Judging by the increase in property values in the last seven years, the council severely underestimated that target (or the term ‘necessary’ was subject to more pressure than it could reasonably be expected to bear.) The only planning successes that have been achieved are mere pebbles in the avalanche of demand.

Oxford-Cambridge Arc

Upward pressure on Cambridge’s property prices is far from a new problem, and has been noticed and commented on by successive governments. In early 2021, the then-Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government published proposals for an Oxford-Cambridge Arc. Stretching between the two cities, it was intended to support various infrastructure projects, aimed at bolstering the academic and economic environment of both cities, and the villages and towns that sit between them.

Practically, the government had planned one million new houses, a new significant road project, and, robust funding and support for the East West Rail project. Since both universities, and both cities, are significant players in industries like technology, life sciences, and advanced manufacturing, the aim was to rely on commercial and political support from those industries and those they employ.

But that didn’t seem to work. As normally happens when a government shows a whiff of creativity or ambition, the local machinery of obstruction whirred into life. Local councillors expressed concerns about the environmental impacts and sustainability of the ‘carbon-heavy infrastructure and housing’, and various local campaign groups were established to prevent the major infrastructure pieces (viz the expressway and the East West Rail). Meanwhile, the NIC reported that “rates of house building will need to double if the region is to reach its economic potential” but that "housing settlements are being held back by a lack of infrastructure”. And after the tenor inside the Conservative shifted away from growth in the wake of the Chesham and Amersham by-election, the government dropped the housing target entirely and handed the project off to the local level, forever to consign it to the mediocrity of the achievable.

And so here we are, in the foggy hangover of the Oxford-Cambridge Arc. An excellent plan that needed strong central government support, and consistent central government energy, to override the all-too predictable reticence from local communities and the environmental lobby. Support and energy that was, equally predictably, never quite forthcoming enough.

Conclusion

Well into the 20th century, Cambridge was essentially a backwater town with a university attached to it. It had some regional administrative and economic importance to the impoverished rural community in the fens, but its national significance was entirely a function of the University it hosted. Today it is a city of global cultural and economic importance.

But it has managed to achieve this cultural and economic importance in spite of its approach to planning, not because of it. The city of Cambridge is a fundamentally conservative place, welded to the past by the inertia of the comfortable and the protectionism of the unimaginative. Since Holford and Wright’s explicit target to curtail the growth of the city, the city has only grown reluctantly, while for demand to live there has increased significantly.

In part two, I’ll explore what it would take to expand Cambridge by 250,000 additional people, and show that the city can, in fact, support it.